The Episcopal Diocese of Chicago recently announced that it is attempting to sell diocesan headquarters, located at 65 E. Huron Street and known as St. James Commons. In conjunction with that announcement, the neighboring cathedral announced that it may be forced to close if that happens, on the basis that a sale will leave the cathedral saddled with expenses it cannot cover.

To that, I reply, “You say that as if it were a bad thing.”

In other words, while I doubt it will happen, it’s no biggie if if does. In fact, if the current cathedral were to close, that could be in everyone’s best interest, including the cathedral’s.

Hear me out.

Background

For starters, this isn’t the first time the diocese has tried to sell the five-story, late mid-century modern heap it calls headquarters. In 2008, a previous agreement with developer Related Midwest to build luxury condominiums on the site collapsed in the face of the Great Recession.

To understand the issues at play, it’s also important to understand the relationship between the cathedral and the diocesan office building. Simply put, the office building and the area in front of it are referred to as “St. James Commons” for a reason, and that is that the office building and cathedral are part of an integrated campus.

The origins of this arrangement date to 1955, when the parish of St. James was named the diocesan cathedral. At that time, the parish signed over title to its parish house and rectory to the diocese. As part of the deal, both buildings were razed and the property used for construction of St. James Commons.

But when St. James Commons was built, it wasn’t built as a standalone office building.

Instead, the two buildings share an HVAC system and other infrastructure. Some of the space in St. James Commons is almost exclusively used by the cathedral, including the sacristy and acolyte rooms.

Other space is shared, including offices, rooms for social events and meetings, and the elevators, which provide ADA accessibility to cathedral users. athedral uses space in the headquarters building for offices, social events and meetings, while the elevators provide ADA accessibility to cathedral users.

Further complicating matters is that, less that four years after the previous abortive effort to sell St. James Commons, a capital campaign was held to deal with all the deferred maintenance that had been allowed to accrue prior to the redevelopment effort.

As is often the case in these situations, donors didn’t fully understand that this was a game of catch-up, versus teeing up for the future. Thus, Anglican Watch has heard from several donors who are taken aback that, just eight years later, the property is up for sale. If we were going to keep trying to sell it, they say, why did we remodel it? Why not just continue to let things slide?

This prior capital campaign to improve St. James Commons, cathedral officials claim, is making the cathedral’s current $16 million capital campaign challenging, even as they try to raise money to replace the pipe organ, deal with decaying masonry, and replace the roof.

Additionally, the potential need to replace HVAC and other infrastructure due to the sale, as well as to find office and meeting space for cathedral staff and ministries, undoubtedly will be difficult for the cathedral. That, despite the fact the cathedral is promised a portion of the proceeds from the sale of St. James Commons.

The biggest wrinkle

But the biggest wrinkle in all of this is that the diocese has foolishly been subsidizing its $5.1 million annual budget from investments. At the current rate, these funds will be deleted by 2025. And $750,000 of that annual budget is the cost of maintaining the office building.

In other words, the diocese is on a fast track to financial calamity if it does not offload the building.

But to an astute real estate developer, that also means a fire sale is in the offing. So why would a developer pay big bucks for the property when it can snag it for next to nothing simply by biding its time?

Nor is having a cathedral next door advantageous any more. Gone are the days when big developers were Episcopalians, church attendance was normative, and people welcomed a church as good neighbors. In fact, most high-end projects suited to Chicago’s Miracle Mile would probably be just fine without the cathedral and its food ministry nearby—read homeless persons.

At the same time, the current offering talks about affordable housing as part of the deal, but not necessarily on site. Thus, as postured, the deal is unlikely to be of much benefit to marginalized communities.

As to the sale price, the current surge in inflation, labor costs and interest rates are going to be baked into any offer that comes along. Combine this with the fact that time is not on the diocese’s side, and it is unlikely that the diocese will do well in the transaction. Indeed, when all is said and done it may have to settle for simply getting out from under the expenses associated this antiquated, Madmen-era heap.

But what if the cathedral does close?

So what about the risk to the cathedral and its finances?

Let’s be clear: Given the aging demographics of the Episcopal Church, if you are worried about money now, you should be damned worried about what your finances will look like 10 or 15 years from now, as us baby boomers die off.

As things stand, right now the cathedral is in pretty decent shape, at least on the assets side.

Per the Episcopal News Service, the cathedral holds investments of $9 million and is in the process of a $16 capital campaign.

But looking at revenue and attendance, things don’t look so good. Yes, the cathedral is growing — a rare thing within the denomination. But as of 2020, average Sunday attendance was 353, while pledge and plate were $798,495, on a par with mid-sized suburban churches.

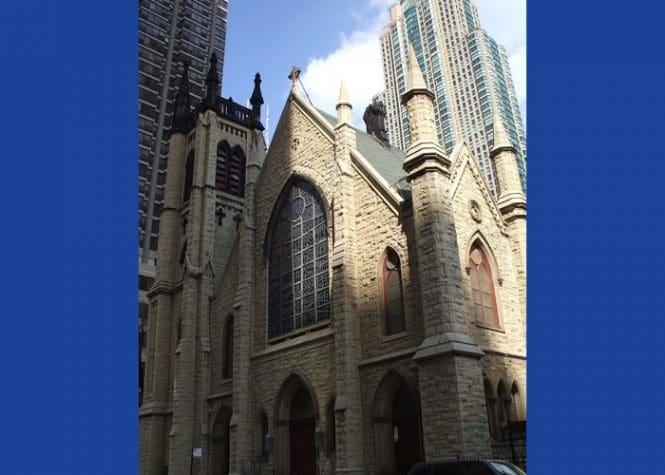

I get it. The building is historic, and it’s pretty. People are attached to it.

But it lacks insulation, has very little space of its own for meetings or community outreach, and sits almost on top of Chicago’s famed Miracle Mile. Great for upscale restaurants and luxury condos. Not so great for reaching marginalized communities.

And the proposed sale does little to help with mission. While it references affordable housing, as currently envisioned the transaction does not require on-site affordable housing. That speaks volumes to the problems ungirding the proposed sale.

My proposal

So, my proposal is simple: This may be the time to take seriously the cathedral’s tagline on its website, “Restore. Reimagine. Rebuild,”

In other words, take the cathedral’s extensive wealth, and cash out. Forget about stringing things along to get a building from the 1860’s into the next century. Instead, focus on having a building that will meet next centuries’s needs. Maybe even ask the question, “Do we actually need a cathedral?”

In the next 20 years, there will be lots of church buildings on the market. Even more will be underutilized. I am pretty sure the diocese can find somewhere to plop the bishop’s chair. The early Christians did just fine without a cathedral. Modern Christians can too.

Also worth considering is the changing role of cathedrals over the millennium. For example, in medieval times cathedrals were centers of learning, places of safety and refuge, waystations for pilgrims, centers for medical care, and focal paints for the community.

Today, other than the occasional concert, cathedrals often have little connection with the surrounding community. Instead, they become insular little communities, where people do church, inside of being church. And they are stages for streaming video and conducting the big Christmas and Easter extravaganzas. Yes, they may serve meals and help the homeless, but they are not the community centers that cathedrals were 500 years ago.

So what does it mean to be a cathedral? And what will it mean in 100 years, assuming the Episcopal church makes it that long?

None of us know the answer. I certainly don’t. But it’s clear that the cathedral’s current planning hasn’t even asked those questions. Instead, it’s all about returning the building to past glory—a past glory, that as discussed previously, is likely inconsistent with the wishes of potential developers.

Nor are churches fun to have as part of a building project. Just ask around and see what most builders and subcontractors think of churches. Few will give you a straight answer, but you’ll find that many that won’t touch a church with a 10-foot pole.

Why?

Because churches are perceived to want everything yesterday, at half price, and with 40 free modifications to the project, all at no extra charge. Oh, and don’t get the place dirty while you’re working.

So, before the cathedral gets in the thick of that quagmire, there’s a good argument to be made for either selling the cathedral along with St. James Commons, or donating it as a museum. Not only does that free up a wide range of possibilities for the future, but it avoids spending the next few years next to a muddy, noisy, messy construction site.

Instead, take the cathedral’s extensive assets and the money it is gathering for its capital campaign and find a place where a cathedral could really make a difference in turning around a blighted neighborhood. Where it could make a difference in the lives of others. Then, build a structure that’s energy efficient. That really is a community center. Where people go to seek sanctuary, medical care, and learning. Where people find jobs. Where people can access child care and computers.

And maybe that doesn’t come with a pipe organ. Perhaps stained glass won’t be part of things.

But the things that really matter, like care for neighbors and the environment, could take the lead. And freed from the ongoing expense of maintaining an ancient building, designed for an 1860’s congregation, the church could perform a real miracle.

It could become a cathedral for the 22nd century. It could grow, thrive, and make a difference in the world.

– Editor

The episcopal church could do a lot of good as a legacy. John Shelby sprong was right. The theology is dumb but the spirit of the church could live on. Imagine if the church took its billions and just focused entirely on helping people