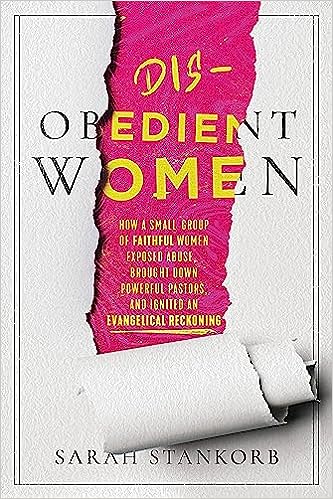

We were delighted to binge-read Sarah Stankorb’s book “Disobedient Women.” The book covered several friends in the blogosphere, including Dee Parsons, Christa Brown, Julie Anne Smith, and Amy Smith. Specifically, the book talks about how these courageous women responded to abuse by speaking out, and in so doing blew the whistle on sexual misconduct, misogyny, and the other problems that for too long simmered beneath the surface in evangelical denominations.

And while Stankorb’s book didn’t touch directly on the mainlines, the Episcopal Church (TEC) should not ignore the lessons we can draw from the book.

What are those lessons?

The status quo

Let’s start with the status quo. Almost all organizations seek a steady state. And once they find that perceived constant state, they often fight to avoid change.

Hand in hand with this stasis runs another trend: avoiding the unpleasant. Whether it’s sexual abuse, harassment, bullying, a toxic culture, or other unpleasant truths, organizations typically proclaim their opposition and fight to avoid doing anything about these matters.

And while TEC likes to think of itself as at the vanguard of social justice, in many ways, it lags behind the ELCA, the Society of Friends, and others.

Indeed, TEC often is profoundly reactionary. For instance, it clings to creaky old real estate, venerates an increasingly obsolete prayer book, and loves its tired and trite Victorian hymns.

And heaven forbid change enters most Episcopal parishes. For example, while the church talks about the need to grow, just suggest inviting the neighbors to a church social event.

If yours is like most parishes, you’ll get a look like you just proposed having Satan officiate at Easter Mass.

Things get even trickier if you buck authority. The canons may say the vestry is responsible for the church’s temporal affairs. But suggest something essential to a rector who can’t be bothered — like cleaning up facially inaccurate financial reports — and you’ll quickly find that clericalism beats canon law every time.

Similarly, complain about abuse, and clergy and laity alike will call you a domestic terrorist, claim you’re harassing people and more.

Jesus cared for the poor and welcomed the oppressed.

Yet far too often, TEC ignores the former and creates the latter.

The power of one

The disobedient women in Sarah Stankorb’s book faced many of these issues.

But instead of slinking away quietly, as Episcopalians are wont to do, these women stood up and spoke out.

Predictably, they have paid a heavy price. This ranges from name calling (daughter of Stan being an auto-correct fave), to defamation lawsuits, to fabrications that their marriages were in trouble when they weren’t.

But over time, these women not only blew the whistle on sexual abuse in the Southern Baptist Convention. They have also called out bullies, abusers, and other low-lifes in the Gospel Coalition, the Presbyterian Church in America, the Catholic church, and the Episcopal Church. (Thanks Dee!)

Ironically, we see few with the same backbone in the Episcopal Church, either male or female. Yes, folks bloviate about resisting injustice and oppression, but in most cases, it’s nothing but empty Jesus-babble.

As for seeing people actively resisting injustice and oppression, Episcopal responses run the gamut.

On the one hand, nothing is funnier than watching Episcopalians rolling into a diocesan convention, arduously pretending they can’t see protestors outside.

On the other hand, there’s nothing more damning than seeing people leaving Sunday Mass at an Episcopal Church only to flip protestors off as they leave the parking lot. Couldn’t wait until you got off church property, huh?

Or dropping the patronizing, “you just need to get a job,” which is hugely amusing. Have one, pays more than you ever made, now happily semi-retired. (This ageist slam says a lot about TEC demographics when some old codger in a Lincoln says that to someone in their 60s.)

Nor is the TEC House of Bishops any better. Indeed, even when confronted with allegations of child rape or molestation, many will sit silent. Or worse, cover up situations of sexual harassment.

Relatedly, while evangelicals can be profoundly ugly when confronted with criticism, most do better when confronted with protestors than do Episcopalians.

For example, picket a conservative church; many will bring you coffee and donuts or offer to let you use the restroom. Episcopalians won’t try to engage but will either try to ignore you, curse you out, or call the police. (It’s called the First Amendment. Even Donald Trump knows what it is.)

In all this, we see very few Episcopalians who work for justice and peace or resist injustice and oppression. And even fewer who understand that even a single individual — disobedient woman or disobedient dude — can make a difference.

In short, TEC trades virtue-signaling for the hard work of actually striving for justice and peace. And if you want a real eye-opener, ask former Episcopalians about the abuse they have experienced in the denomination or the feckless response from people who see it happening.

Of course, that runs counter to the huge investment of time and resources these disobedient women have made in telling the truth.

Opening doors

There’s another aspect of these disobedient women that Stankorb covered–one that many didn’t even realize existed until now. That aspect is their willingness to cover topics that would usually be off-limits to mainstream reporters.

By covering these stories, which many mainstream publications considered too risky, potentially defamatory, or internal church affairs that should be addressed internally, our fellow bloggers made it possible for traditional outlets to cover abuse in the SBC, the Catholic Church, and elsewhere.

That begs the question: what would happen if TEC used its social media presence to call for social justice? Not abstract, feel-good things like structural racism, but issues with specific names, dates, and people? And what if the church told the truth about its conduct in specific situations? Like people it has hurt, abused, maligned, or bullied?

What if it opened doors to justice by dealing with problems in the here and now versus waiting 100 years to address slavery–after victims are dead and gone?

And what if the church promoted a culture in which people were expected to resist injustice in the here and now versus flipping people off? Or trying to push them out of the church? Or ignoring the issue?

Of course, that raises issues about the episcopacy itself. What if bishops in the Episcopal Church made clear that misconduct won’t be tolerated? Or dioceses told clergy, “We have a zero-tolerance policy for abuse of any sort,” and enforced it?

We also can back up a step. Assuming a zero-tolerance policy isn’t possible, what if the church held itself to the mediocre standards of publicly traded companies? Like a churchwide hotline for fraud, waste, and mismanagement? Or immediately holding bishops responsible who sexually harass women or engage in retaliation for reporting it? Or taking disciplinary action against any priest whose parish doesn’t perform an annual audit and get a clean audit report?

Looking ahead

From where Anglican Watch sits, the biggest challenge confronting the Episcopal Church isn’t declining revenues or plummeting membership. Instead, the make-or-break issue will be operating with integrity–being church versus doing church.

Many people in our society yearn for connection.

But they don’t want fakes, frauds, bullies, or narcissists.

Nor do they want to shell out big bucks so some pampered prince can spend summers on the beach, weekends golfing, and generally living the good life, even as they do damn little to earn this lifestyle.

The changes that need to happen in the Church will require courage. The courage to speak up, name names, say no mas, and quit making excuses for the church’s often abysmal behavior.

Making those changes happen will also require addressing clericalism and expecting clergy to lead exemplary lives. It will mean less self-care and more other care.

And it will mean disobedient women and disobedient dudes need to be willing to follow the paths of these courageous and fearless women.

So, Sons of Stan and Dudes of Darkness unite. It’s time you climbed on board before the Disobedient Women, aka Daughters of Stan, leave the station.

Leave a Reply