Anglican Watch is keeping a finger on the pulse of several Title IV cases, including the case at St. Thomas, Fifth Avenue. In every instance, church officials are making a mess of things and, in several instances, making false statements about the cases.

We therefore want to clarify several things:

Title IV is NOT confidential for victims

The Title IV clergy disciplinary canons expressly apply only to clergy (Canon IV.1), with the exception of one minor recent tweak that’s not relevant to this post. As a result, laity or persons who are not members of the Episcopal Church are NOT obligated to maintain confidentiality.

That’s important, because we’ve repeatedly heard intake officers and other judicatories say that the intake process is supposed to be confidential. That is true, but only as to clergy.

Indeed, it is inherently abusive to try to silence victims. That’s even more so the case when abusive behavior directly or indirectly results in one or more victims leaving the church, or the Christian faith.

To be clear: The victim’s story is theirs to tell and they get to decide who tells it, when, and how.

The church does not get to dismiss complaints, then insist that its misconduct in doing so be treated as confidential.

In saying that, there’s one caveat, and it’s an important one.

Specifically, victims who wish to share their story need to be cautioned that coming forward almost certainly will result in retaliation from members of the congregation. Such behavior is inherent, given the disparate power dynamics between laity and clergy offenders.

Thus, victims should be cautioned before coming forward about the possible consequences of disclosure.

Title IV does not mandate absolute confidentiality for the church

Absolute confidentiality is neither expected nor guaranteed at ANY phase of the Title IV process. The canons repeatedly and expressly provide that, as part of the disclosure essential for a meaningful pastoral response, the bishop diocesan may disclose information in his discretion. See Canon IV.6.13 and other references.

A pastoral response is one of the first and highest priorities at all phases of the Title IV process

A pastoral response to ALL affected parties is required under Title IV. It is the bishop’s responsibility and is not optional.

To be clear, a pastoral response is NOT the same as pastoral care, although pastoral care may be part of a pastoral response.

Instead, a pastoral response is a a structured response intended to facilitate “healing, repentance, forgiveness, restitution, justice, amendment of life and reconciliation among all involved or affected.”

Here’s what church training materials have to say:

So, why have we seen no meaningful pastoral response from the Diocese of New York in the St. Thomas case?

Special provisions for a pastoral response in cases where sexual misconduct is alleged

Relatedly, there are special provisions for a pastoral response when allegations of sexual misconduct are involved, as is the case at St. Thomas Church Fifth Avenue. To date, the Episcopal Diocese of New York has not followed these requirements.

Specifically, Canon 8.1 provides:

If the report involves an allegation of Sexual Misconduct, the Bishop Diocesan shall provide for a professional pastoral care assessment in order to provide an appropriate pastoral response. The pastoral response will include all affected persons and communities. The pastoral care response will be based on the professional pastoral care assessment.

We find the Diocese of New York’s failure to follow these provisions troubling, as the case has been around in one form or another since December 2024.

We have notified intake officer Alison Quinn and Bishops Shin and Heyd directly of our concerns on this score.

Sexual misconduct is broadly defined under church canons

We’ve heard from a couple of people that they think it’s not sex if the behavior in question doesn’t involve intercourse. However, that’s not how the canons look at the issue.

Per Canon IV.2:

Sexual Behavior shall mean any physical contact, bodily movement, speech, communication or other activity sexual in nature or thatis intended to arouse or gratify erotic interest or sexual desires.

Sexual Misconduct shall mean (a) Sexual Abuse, (b) Sexual Behavior engaged in by the Member of the Clergy with a person for whom the Sexual Behavior is unwelcome or who does not consent to the Sexual Behavior, or by force, intimidation, coercion or manipulation, or (c) Sexual Behavior at the request of, acquiesced to or by a Member of the Clergy with an employee, volunteer, student or counselee of that Member of the Clergy or in the same congregation as the Member of the

Clergy, or a person with whom the Member of the Clergy has a Pastoral Relationship. (Emphases supplied)

Thus, even if clergy are not found criminally liable for sexual misconduct, they will still have violated Title IV if they engaged in any unwanted sexual behavior. Such behavior is particularly egregious when it involves a parishioner, as is alleged in the case of the Rev. Mark Schultz.

The standard at intake is to presume that everything complained of is true

This ties to our previous post about how neither the intake officer nor the Reference Panel have any factfinding authority.

At intake, and only for purposes of intake, all matters complained of are assumed to be true.

Thus, the intake officer gets to ask two, and only two, questions:

- Assuming the matter is true, would it be a violation of church canons?

- If so, is it a material violation? In other words, white lies don’t count.

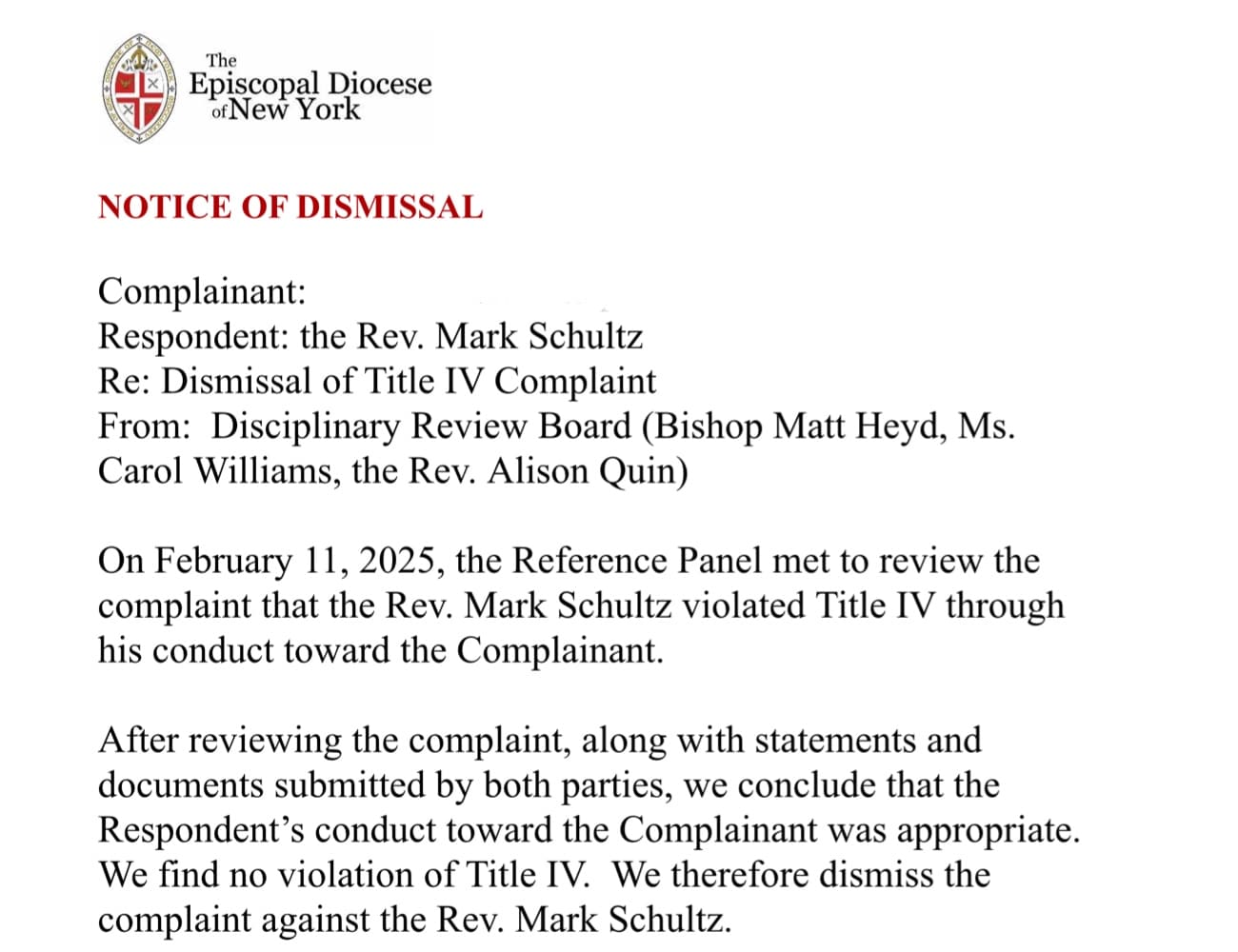

As for the reference panel, its only role is to decide where to send the case for resolution. It has NO factfinding authority—which is why we said that, when the Diocese of NY Reference Panel “found” that Mark Schultz’s behavior was “appropriate,” it was endorsing sexual assault and harassment.

In other words, what was alleged was sexual assault and harassment; that was the issue before the Reference Panel.

Nothing more. Nothing less.

Thus, by “finding” the behavior in question was “appropriate,” the Reference Panel gave its seal of approval on the only issue before it, which was the allegation of sexual assault.

In other words, it’s important not to play games, because when judicatories do so, they come up with outrageous results — like signing off on sexual harassment/assault.

And yeah, we’re pretty sure the Diocese of New York would say, “That’s not what we meant.” But the reality is that’s what the Diocese said when it initially dismissed the Title IV case against Mark Schultz.

That tees up for our next point, which is addresses the importance of not “winging it.”

It’s really important for judicatories to read the canons

Intake officers, bishops, Title IV attorneys, members of diocesan disciplinary committees, and members of diocesan reference panels all need to read the Title IV canons.

Not once, but twice.

Each and every time they handle a clergy disciplinary case.

And they really need to get Title IV training.

We’re getting tired of saying this, but we get super irritated when intake officers and other church officials, often already poorly trained on Title IV, decide to guess at what’s in church disciplinary canons.

Indeed, the canons are constantly evolving, so it’s never safe for anyone to assume they know what the canons say.

And just because someone’s an attorney doesn’t mean they are proficient in Title IV. Indeed, some of the biggest messes we have seen come from church attorneys who’ve been doing Title IV cases for years, resulting in them thinking they know Title IV well—even though their knowledge may be obsolete.

To be clear: Judicatories are dealing with people’s lives and their faith. These are not issues where it’s okay to play fast and loose.

Mistakes in Title IV often can’t be fixed

There’s an unspoken assumption that often lurks right behind the scenes in a Title IV case that, if a Diocese gets things wrong, it can always revisit the issue. If there’s no accord or Hearing Panel decision, that’s true, but the harm to the parties involved often is irreparable when diocesan officials bungle a Title IV case.

Here’s what the Standing Commission on Constitution and Canons says:

A poorly handled Title IV matter can cause unnecessary — and often irreparable — harm to both relationships and reputations of all parties involved. The Church has a responsibility to remediate any unnecessary costs, both relational and financial.

The Church Pension Group does not serve the church. It protects corruption.

We hear this all the time. But the reality is the Church Pension Group (CPG), which is the church’s captive insurance carrier, in no way behaves in a way that supports the Episcopal Church when it comes to misconduct.

Indeed, in several of the cases we are watching, we fully expect that the Episcopal Church will be sued.

Why? Because the church is playing games and monkeying around over allegations of clergy misconduct at the Title IV level and re-traumatizing victims.

But will CPG settle the matter?

If history is any indicator, the answer is a resounding no.

Indeed, CPG strung along the plaintiff in the Chicago child sexual abuse lawsuit, right up until Episcopal bishop Chilton Knudsen was set to give testimony. (She had said that she “vividly recalled” notifying law enforcement and the ensuing conversation — she just couldn’t remember with whom she spoke. Uh-huh.)

To be clear, you should not have to sue the church in order to get justice. The matter should be resolved at the lowest level possible, as quickly as possible, with an emphasis on caring for the victim.

Thus, by forcing victims to litigate, both CPG and the dioceses it claims to serve do a profound disservice to all involved, while undercutting the church’s claim to be “loving, liberating, life-giving.”

The church cannot say anything to the complainant about a Title IV proceeding or its status

To the contrary, the intake officer is required to provide monthly updates per Canon IV.6.10, which provides:

The Intake Officer will report at least monthly to the Respondent, the Respondent’s Advisor, the Respondent’s Counsel, if any, the Complainant, the Complainant’s Advisor and the Complainant’s Counsel, if any, on the progress in the matter. Should the Intake Officer not report at least monthly, the Respondent or the Complainant may petition in writing the President of the Disciplinary Board who must provide a report in writing not later than 15 days from the date of the petition to provide the reports.

So far, we do not believe monthly updates are being sent in any of the cases we are monitoring. We also have exercised our rights in the cases in which we are the complainant to demand these reports.

Leave a Reply