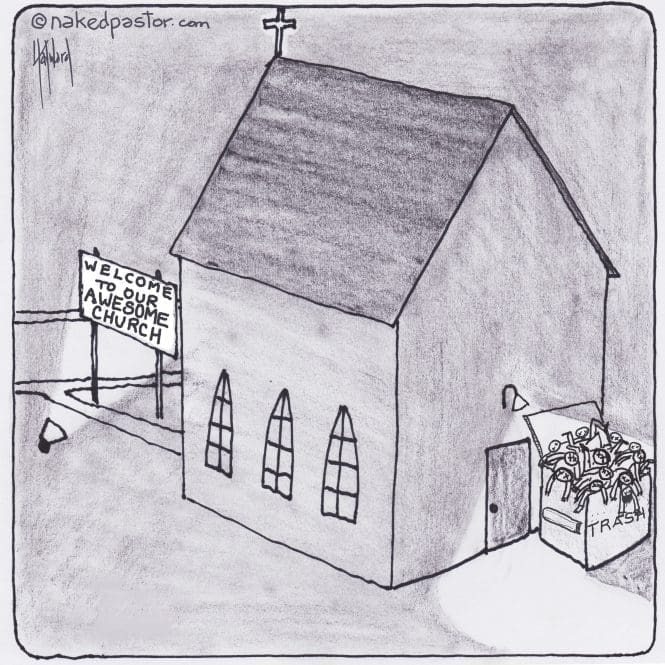

If there is one thing Episcopalians and the denomination are not good at is conflict. But that’s not to say that members don’t have ways to respond when church officials ignore conflict. Indeed, we are seeing an increase in quiet quitting, where folks just show up less and less, before eventually moving on to another church.

For starters, this approach fits with church dynamics. Like most churchgoers, Episcopalians are very conflict avoidant. Unless it’s their conflict, in which case it’s DEFCON 1, all hands to battle stations, get the launch codes ready.

So quietly not showing up avoids painful discussions and the possibility of one of those world-class Episcopal squabbles, all while being easy and convenient.

This is reflected in the discrepancy between membership numbers and Average Sunday Attendance (ASA). Many churches claim membership in the hundreds or even thousands, despite the fact their facilities don’t even hold that many people. But look at ASA and you’ll see many of these same churches are on a roll if they turn out 200 on a Sunday.

To be fair, some of this is due to the lackluster Episcopal definition of membership. Three times a year? Christmas, Easter, and one Sunday when you’re bored, with nothing better to do. That’s pretty sad.

And yet, this disparity between membership and ASA is not born of laziness. It’s due to lack of anything to draw people to the church. And it’s due in large measure to the church’s dysfunctional dynamics.

Yes, the pandemic led to many getting out of the habit of attending church. Or, if they do, they do so from the comfort of the living room, coffee in hand, bathrobe, fuzzy slippers and all.

That raises an important aside: the church needs to think carefully about the relationship between virtual attendance, quiet quitting, conflict, and money.

Just as some Anglo-Catholic parishes often serve as the last stop on the road back to Rome, virtual membership is often the last step towards non-membership. That’s particularly true in churches in which there are high levels of unresolved conflict, which provides a powerful incentive towards the Twitter-is-free model of membership.

Go to the livestream, watch the service, enjoy the music, and avoid catty altar guild folks, bullying choir members, and narcissistic clergy. It’s the Episcopal version of Miller Lite—all of the taste, less calories. And let’s face it—we haven’t seen major changes in the liturgy in decades. It’s not like we’re going to miss something new and spectacular if we attend via livestream.

Even better, virtual membership costs participants nothing. Gone are the days of awkward discussions about pledging, or pressure to “get involved” and join the altar guild, the grounds committee, the vestry, or any of the one-thousand-and-one ways the church tries to rope you into doing church.

So unless the church plans to start profiling online members and selling the data, it’s time to think about how it’s going to monetize those online pseudo-members. And with record numbers of us baby boomers headed to the Great Disco in the Sky over the next 20 years, it’s a fool’s paradise to rely on a smaller and smaller number of members giving more and more to keep the creaky old heap going.

Nor is quiet quitting confined to those on the margins of the church.

Many who quietly quit are devout members, deeply engaged in the church.

Indeed, in this author’s former church, one really likable individual who had faithfully attended EFM for years and been a constant at Sunday worship started showing up less and less often. Sure enough, later on I got a message from him saying he’d concluded the church was abusive and moved on.

Tellingly, no one in the church reached out to him and asked, “Can we talk?” In the words of British rock group Queen, “Another one bites the dust.” Too bad, so sad, catch you in the rebound.

In those cases, it’s not unusual to see others quietly follow. Seeing someone else quietly disappear provides an incentive to do the same, and the combination of unresolved conflict and the indifference to the loss of members makes it all the easier to pull the plug.

Nor does the Episcopal Church routinely call members to find out why they left. Indeed, ask around and you’ll find many former members leave with no intention to quit, but get caught up in caring for aging parents, dealing with cancer, job loss, or COVID. But when the ill winds pass and they realize no one bothered to reach out to them to find out why they were missing, they return the favor and go silent. (We know of only one parish that routinely contacts inactive or former members. Here’s looking at you, Stinkbomb.)

Speaking of COVID, its role is often misunderstood.

While many churches stood empty, with no weddings, funerals, worship or Sunday schools, clergy had plenty of time on their hands. Yet many elderly members, if willing to engage candidly, will say how profoundly lonely and abandoned they felt during the pandemic. No visits, few calls, no cards, no care packages. Same for young families, those in crisis, and others at liminal stages of life.

In short, COVID made clear that the emperor has no clothes. Loving, liberating and life-giving? Not so much.

Clergy misconduct and diocesan handling of these issues also plays a huge but poorly understood role.

Anglican Watch has seen waves of quiet quitting in churches and parishes we have covered in which there has been clergy misconduct, especially when the approach to the resulting conflict can be best summarized as “nothing to see here, just move along,” followed by the usual Jesus-babble about love. Or, as is often the case, a bungled diocesan response.

Nor is the church unaware of the damage caused by its feckless attitude towards conflict and clergy discipline. The Title IV process is intended to facilitate healing and reconciliation, but typically such a complaint is mishandled. The result, per the church’s Standing Commission on Constitution and Canons:

a poorly handled Title IV matter can cause unnecessary – and often irreparable – harm to both relationships and reputations of all parties involved. The Church has a responsibility to remediate any unnecessary costs, both relational and financial.

As to ignoring informal complaints, that’s not Christian. Nor is it about love; it’s selfish avoidance. Or, as Bon Jovi puts is, “You give love a bad name.”

And so it is with St. Paul’s Alexandria, where members of the vestry and executive committee are increasingly making themselves scarce as rector Oran Warder tries to slap a layer of nice on the fact that the church had an alleged torture profiteer as warden, and ignored the fact when it became public.

Yet the church moved mountains to fire an elderly employee, near retirement, who made an irreverent comment about Warder “throwing his dick around.” She apologized, so this should have been a small matter indeed in the larger scheme of church life. But Christian forgiveness only extends to alleged torturers; the sacred member must be protected at all costs. That’s the lesson to be learned from the way Christianity is practiced at St. Paul’s.

Similarly, other churches and dioceses we have covered are showing record numbers of quiet quitting. Many are not seeing huge reductions in cash flow due to a ramping up of giving by the “righteous remnant,” but count pledging units and look at the average age of members, and there’s a perfect storm in the making.

Indeed, in this author’s former church, 60 percent of pledging units have flown the coop. With only about 160 pledging units left and a large physical plant, plus the ravages of inflation and membership that is overwhelmingly baby-boomer, the loss of even a handful of pledges will spell big problems.

And it’s not going to get better any time soon, since the church continues to try to brush aside its past misconduct. After all, it wasn’t sin—it was a mistake. And it happened before I got here. So there.

Similarly, while the effect hasn’t fully hit, we are prepared to bet that members of St. Paul’s (Purcellville Va.) are going to quietly quit when they contrast Tom Simmons’ foolish chatter about “pansexualism” with his own affair, replete with randy emails, ads on dating apps, allegations of drug use and misconduct towards his own children. Yes, the church’s budget is running a little ahead of schedule, but over time this is expected to changed.

Thus, while we’ve never been quite sure what “pansexualism” is, we’re pretty sure a good starting point would be Simmons’ personal life.

There’s another issue at play in the whole quiet quitting phenomena, which is that very few churches distinguish between the average and the mean when it comes to pledges and the connection to quiet quitting.

Every church has members who are amazingly generous, writing checks of 60K or more on an annual basis, resulting in a much higher “average” pledge than would otherwise be the case.

And while many rectors are good at sniffing these folks out and making sure they serve on things like the finance committee, lose one or two of these folks and the church is in a world of hurt.

Even those churches with million dollar budgets, which often spend every last penny that comes in, face drastic cuts when this happens.

Nor will the loss of these individuals be prevented by keeping them engaged in the parish, for many are retirees who are gifting down their estates as they go. In other words, no matter how things play out, within the next 20 years, the revenue stream coming from these members will stop.

Indeed, this author’s childhood parish in western PA, which used to be flush with older members who gave generously, now lives almost exclusively on its endowment. Indeed, services are so empty that it doesn’t really matter what the finances look like; there’s very little Christian community to be had when the ASA is 20 people.

In short, if TEC is to survive, it needs to:

- Become beloved community to all persons.

- Hold itself accountable.

- Hold its clergy accountable.

- Be willing to let go.

Apropos the latter, there are hundreds of churches out there in lovely old Victorian-era buildings. They’ve long been fixtures of the community and are much beloved, but look behind the scenes and you’ll see failing roofs, bad boilers, issues with asbestos, and energy inefficiency. Indeed, those steep slate roofs look lovely, but it is almost impossible to add insulation, and very few qualified slate roofers remain.

In other words, even those churches that can afford repairs on aging physical plants are, in many cases, well-advised to move out and use the funds, while they still have them, to transition into modern, energy-efficient facilities that can serve as true community centers, versus decaying old heaps that bespeak a church out of touch with the times.

Similarly, the archaic notion of a full-time priest who’s congenial, gets paid six figures to be a “professional Christian,” and is available night and day for pastoral emergencies is fast falling by the wayside.

Indeed, many full-time priests don’t do pastoral emergencies at night. That’s what hospital and police chaplains are for.

And where but the Episcopal Church do employees get so much time for “self-care”? Many of us in the private sector haven’t had a day of vacation in years, let alone sabbaticals, four weeks at the beach in the summer, and more. And to be blunt, we’re not so enraptured by clericalism that we are willing to subsidize that sort of lifestyle.

In other words, the quiet quitting will continue until one of two things happens: 1) The church cleans up its act; or 2) The church ceases to function as we know it, consisting instead of Trinity Wall Street, possibly the National Cathedral, a few well-endowed but empty churches, and a smattering of what have essentially become home churches.

As things stand, it’s looking more and more like the correct answer is number two: The church is circling the drain and not willing to do anything about it.

And folks—the evidence is there for all to see. Absent revolutionary change, we are down to the last few Easters of the Episcopal Church.

Leave a Reply